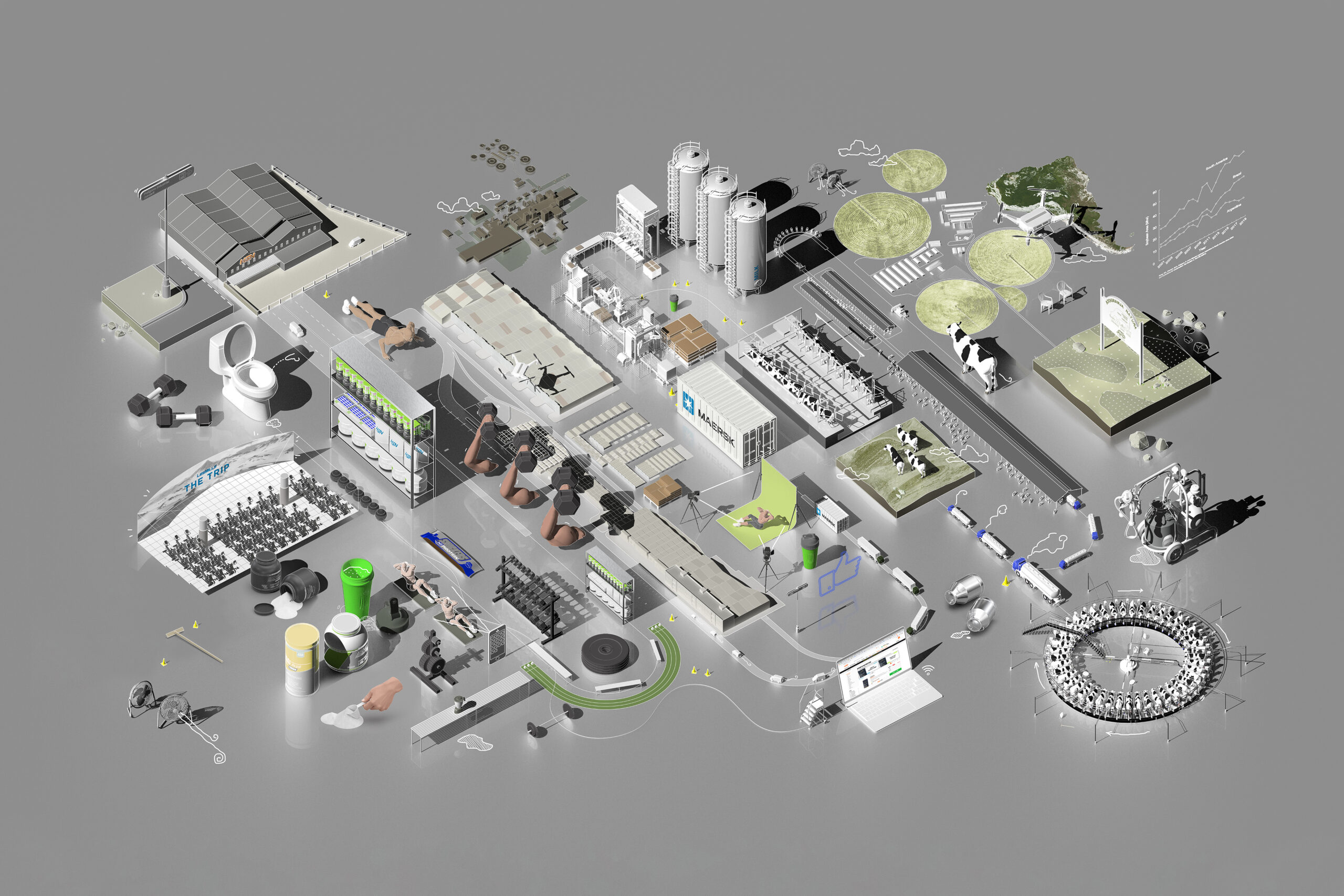

“Protein Clickbait for the 14%” is Common Accounts’ contribution to FOODSCAPES: the Spanish National Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale.

FOODSCAPES, curated by Eduardo Castillo-Vinuesa and Manuel Ocaña, “is a journey through the architectures that feed the world; from the domestic laboratories of our kitchens to the vast operational landscapes that nourish our cities. At a time when energy debates are more pertinent than ever, food remains in the background, yet the way we produce, distribute and consume it shapes our world more radically than any other energy source.”

Common Accounts’ contribution is one of ten recipes presented in the pavilion that interrogate contemporary nutritional supply chains and the landscapes that feed them.

Protein Clickbait for the 14 Percent

Or, how to make a protein shake to geo-engineer seven million Spanish bodies

Ingredients

Minimum 1 online avatar

An endless stream of influencer thirst traps (suggested serving of 3 bubble butts per minute)

A barrage of encouraging slogans

1 Personal trainer illuminated by a ring light on Zoom or IRL

60 minutes of exercise broadcast via livestream

Post-exertion dopamine stimulation

90,000kg of pasture flora, hay, and silage or 600,000kg of imported soybean fodder

4 to 6 Million liters of water per day

3 Dairy farmers

1 Veterinarian

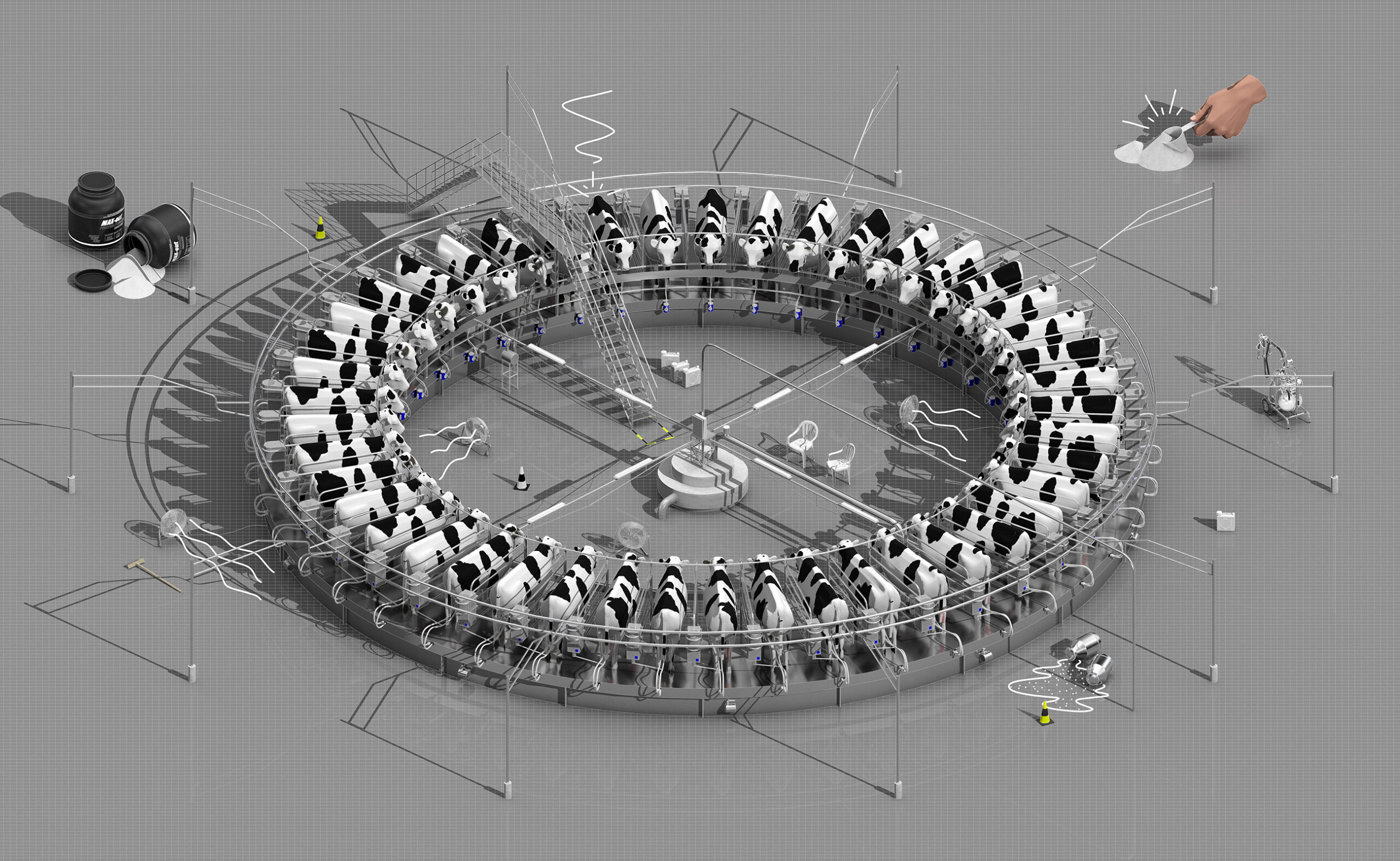

1 Rotary milking parlour

1 Mobile cold liquid product storage tank

A fleet of semi-trailers, added incrementally

1 Whey plant with drying tower

1.5g Stevia leaf extract

2g Natural vanilla flavour

1 Powder packaging assembly line

1 Dry goods warehouse with humidity control for the storage of packaged powder

1 Sports nutrition retail location

1 Blender

Post-consumption serotonin release

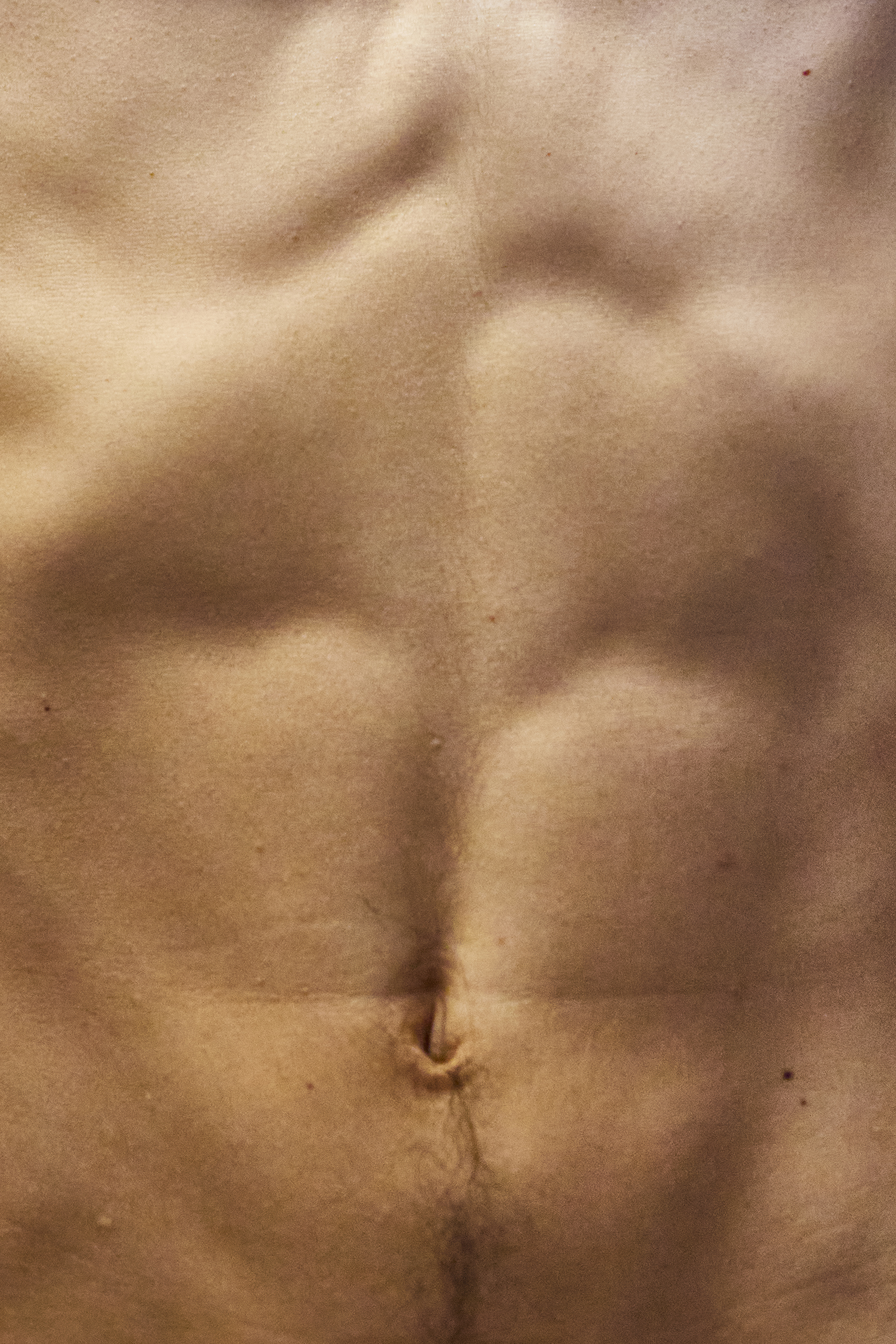

1 Muscle group

1 Toilet

Instructions

Terraform yourself in a few easy steps!

Whey protein powder is a dairy-based meal supplement. It’s an ingredient in medicinal food, baby formula, and sports nutrition products that deliver a high concentration of protein in a single serving. Over recent years, whey protein powder has become associated mostly with physical fitness and gym culture. Its main form of consumption is the protein shake.

A protein shake is a home brew of sorts, the ingredients of which tend to vary based on personal tastes and diets. In a single scoop of typical whey-based powder, which comes in a variety of flavours and can be mixed into water or milk, one is likely to consume 25 to 30 grams of protein. Protein contains amino acids essential for muscle growth, which is why protein-rich diets have been hyped by large segments of the fitness industry as critical to transforming the body into idealized forms (while others stay committed to “natural,” supplement-free growth).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, fitness and wellness resonated with people looking to build up resilience and to invest in their own anatomical wellbeing and self-image. The mainstreaming of protein shakes and added protein products is noticeable on supermarket shelves where any product that can boast added protein will do so—and this justifies their higher prices. The Harman Group market consulting firm determined that 60 percent of North Americans actively seek to consume more protein today, and a 2021 Fundación Mafre study estimated that up to 14 percent of the Spanish population consumes protein shakes. The millions of cows whose milk goes to cheese and whey factories operated by dairy multinationals and food industry brands contribute to the 11 billion USD global whey protein market, which is forecast to grow at an annual rate of 5 to 7% by 2030.

This increasing appetite for protein has been further intensified by the flooding in social media of content that aims to endlessly feed our libidinal desires and bombard us with a disproportionate number of athletic physiques. As the sports nutrition industry continues to grow, it relies on dairy farming and subsequent whey production as the source of its key ingredient. As such, idealized bodies can be linked to GMO soy plantations in the United States and Latin America. In South America in particular, the expansion of soy farming for cattle feed is evident in the colonization of savannahs, forests and extant farmland which now yield much of the fodder used to fuel large dairy farms around the world.[1] The concentration of the protein humans eventually consume in whey form begins in leguminosae (soy, beans, peas), and gramineae (grasses) and can be traced from fields to feed, through cows’ stomachs and udders, to dairies and the powder products that humans ultimately ingest and absorb into muscle fibre.[2] At a typical dairy farm, one finds 3.5g of protein per 100mL of milk in an average daily haul per cow of about 30 liters.

[1] Helen Groome, the dairy farmer who runs a de-intensified, eco-feminist dairy farm in the Basque country which practices an ethos of food sovereignty (and does not contribute to the production of sports nutrition products) has written about the impact of cow feeding regimens on the Global South, informed in part by her academic history in rural resource management. Vista Alegre Baserria.

[2] The protein pipeline often operates as follows: grasses that contain 8-18 percent and soybeans that contain 40 percent crude proteins are consumed by cows who yield raw milk with an average protein content of 3.3 kg/hectoliter, from which roughly 0.7kg/hl whey protein is separated in the process of cheese making, and is eventually reduced once sent to a whey and lactose plant to a concentration of anywhere from 25 to 80 percent protein in its ‘concentrate’ form, and of at least 90 percent protein in its ‘isolate’ form.

There’s Value in the Upstream.

Large whey protein powder producers like Denmark’s Arla Foods are part of a relatively young industry that first emerged in the late 20th century. Whey is a by-product of cheese production and was once used as fertilizer and feed for farm animals before its potential value— both nutritional and economic— was identified and redirected towards human consumption.

In 1976, Arla first began producing whey protein concentrate at a milk powder plant it operated in an attempt to expand the company’s embrace of bio-circularity in its supply chain. Four years later, it inaugurated the world’s largest whey and lactose factory, Danmark Protein, in Videbæk. Advocates for whey protein argue that the quality of its constituent amino acids is better than that available in vegetable protein, and that it closely matches the protein profile found in human muscle mass, making it easy to absorb.[3]

[3] A new program initiated by Arla Foods in 2022 acknowledges the carbon footprint that protein powder production generates. The company has begun incentivizing more sustainable practices with dairy farmers upstream by paying higher prices for milk produced with less harmful inputs and conditions.

Plan your workout, plan your farm.

Gyms and large dairy farms are similarly organized with body performance and value output as key driving factors— as are most bio-capitalist enterprises. Some farms, such as Granja San José in Huesca which, with 7000 cows, is among the largest in Spain, aim to build self-sufficiency into their supply chain. Vast tracts of land adjacent to the dairy operation permit the planting of feed crops that are fertilized with solid and liquid manure produced on site. According to farmers, the secret to high protein levels in cow milk lies in maintaining the correct humidity in their fodder crop. Fields are watered according to land heat patterns monitored through aerial infrared photography taken by drones. Other farms without the capacity and resources to grow their own feed rely on imports from abroad, like soy. Health issues appear and subsequently veterinary bills tend to rise for herds that depend on soy; despite its high protein content, this form of nourishment is not native to dairy cows’ digestive systems. Where cows that feed on local pasture need only consume 1 kg of grass, hay, and silage per day, those that are fed soy imported from overseas must eat seven to eight times as much. The amount of protein per volume of milk collected remains largely the same in both cases. Meanwhile, the high-tech solution for productive, round-the clock-milk yield appears to be the rotary parlour: a rotating carousel where up to 80 cows are milked at a time, with one entering and exiting every 7.4 seconds.

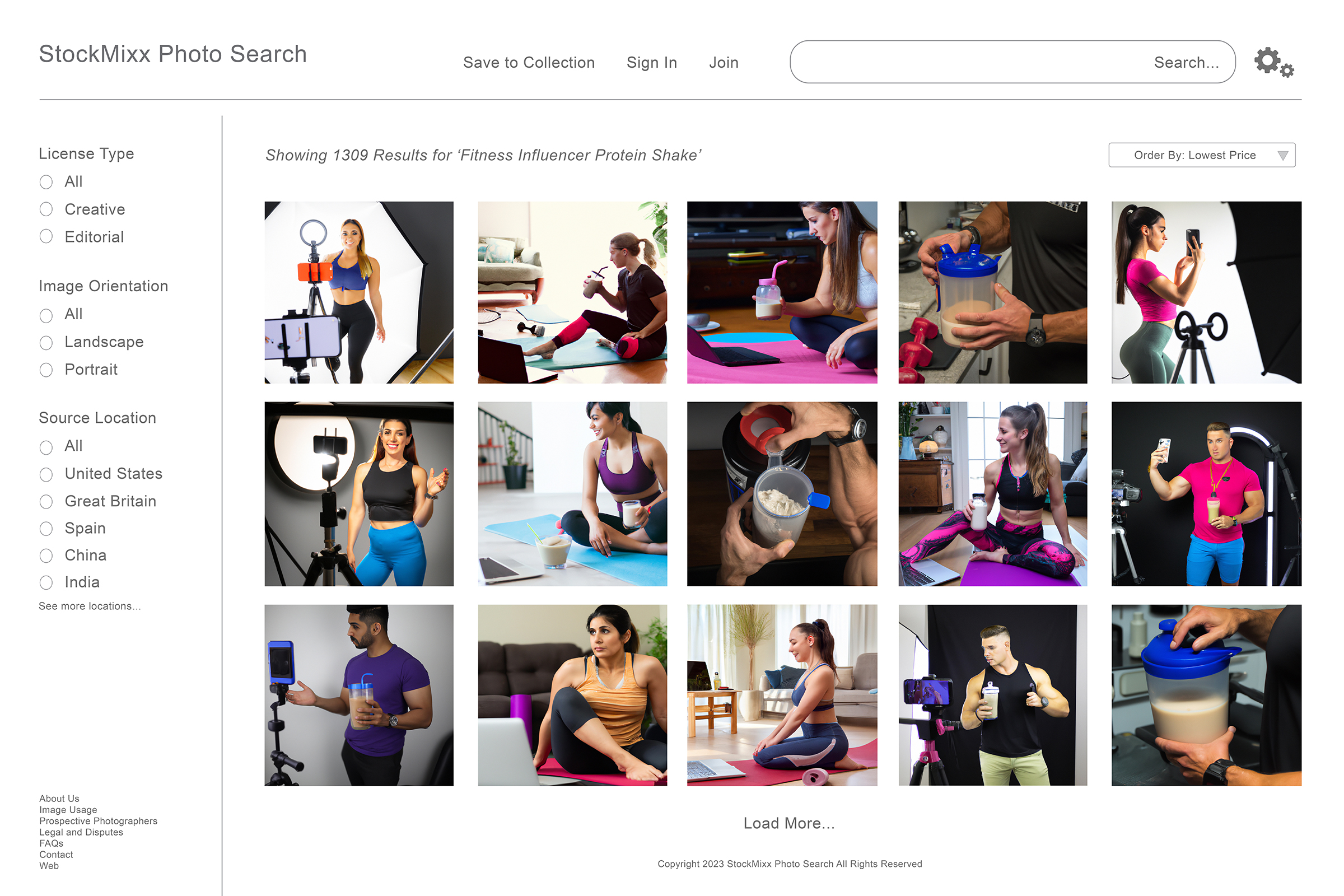

How many “perfect” bodies have you been exposed to today?

Quoting dietician Clare Thornton-Wood, a 2021 article by Sirin Kale published in the Guardian notes that in developed countries, “a protein deficit is very unusual.” A 2018 study in Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, points to research that suggests the human body can only process 20 to 25g of protein in one sitting.[4] Both the United States’ FDA and the UK’s NHS recommend a daily intake of 50g—a target that many people already meet. According to the Nutrition Foundation of Spain (FEN), 30 percent of Spaniards consume more than the recommended amount of protein. Excessive protein consumption can exacerbate pressure on the kidneys and surplus nutrition is simply excreted from the body in urine. Current trends suggest that appetites won’t decline merely because we’re nutritionally maxed out.

The great online is the great outdoors.

Because protein is advertised as being good for us, many people continue to consume it as a supplement and as a substitute of traditional meals, whether they need it or not. And the more people see images of wellness, fitness, and beauty in everyday life, the more they are likely to wish this for themselves. It comes as no surprise then that a significant proportion of sports protein industry advertising takes place on social media with products made available from direct-to-consumer web stores. The sports nutrition industry isn’t merely manufacturing food: it’s developing an appetite in the world. To support this, entire industrial warehouse neighborhoods exist attuned to moisture control, fulfillment, and shipping, all to expand delivery of products from points of sale to the homes of consumers everywhere. These are among the core spatial typologies that characterize the gastronomic supply chain of sports nutrition protein.

[4] Brad Jan Schoenfeld, Alan Albert Aragon. “How much protein can the body use in a single meal for muscle-building? Implications for daily protein distribution.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. Vol. 15, 2018.

The Juncaril Industrial Park in Albolote, Granada, is home to a cluster of sports nutrition wholesalers, retailers, web shops, laboratories, factories, and gyms including Amix Nutrición, EFIT Nutrición, AP Dieteticos S.L., BIOPROX, FitnessKPI, Sport Foods Labs, Balacera Box, Granada Moverte Be More, La Caja CrossFit, CrossFit Five, Musculomanía Suplementos Deportivos, Gimnasio BPXport, MM Fit MASmusculo Gym GRX, OsunaSport Group, ROBIS S.L., Gimnasio Florida, and HSN. The brand HSN has its factory and corporate headquarters in a 12,000-square meter campus which includes a gym and media studio used to film content with their consumable products and brand ambassadors.

HSN’s social media channels are followed by a combined 200,000 accounts. From their web store, customers can order powdered protein, snack bars, vitamin supplements, sleep aids, and a range of apparel. The HSN Logistics Centre occupies a separate site in the eastern section of the industrial park. The district is strategically positioned along major highways and rail lines and is well served by shipping companies who deliver their products from warehouse to consumer. Arla Foods is Listed among HSN’s raw material providers. Their Lacprodan® Whey Protein is mixed into HSN’s hydrolyzed whey protein products.

Render yourself as a model of your community.

Sports supplements that contain whey are derived from real world inputs, but their outputs are purified and concentrated to an extent not found in nature. Their intended ends are synthetic: notions of holistic wellness consumable 24/7 making idealized bodies possible by stripping away other nutrients that might inhibit the sculpting of a torso.

Protein powder is often consumed in or around synthetic environments like immersive fitness studios, or during Peloton, YouTube, or Zoom exercise sessions. Our consumption of it is driven by an awareness of the online world and one’s own image in relation to anatomical forms perceived as ideal. It is theorized that this in turn is driven by a desire for social advantage bred from the enduring concern for survival wired into the human brain.[5] As design curator and historian Carson Chan once asked in the magazine Cura, “What if humanity’s key form of interaction with the world is simply a metabolic one, adding to our biomass as we subtract from the world?” Invoking notions of health and wellness, the whey protein industry has stepped in largely to streamline that metabolic engagement.

[5] Dar Meshi, Diana I. Tamir, and Hauke R. Heekeren. “The Emerging Neuroscience of Social Media.” Trends in Cognitive Science. December 2015, Vol. 19, No. 12.

As our bodies become a site of intensification for the proteins that our desires, landscapes, and factories yield, these places— and the world itself— becomes synthetic as well. The agricultural landscapes that the dairy industry structures to produce feed, raise cows, and extract milk are correlated with the human bodies that those spaces enable to become toned and hardened. Each site – the territorial and the anatomical – has their constitutive regimens and diets, their built-up stores of nutrient rations, their furrowed channels and sculpted topographies, showing an intensification driven by a single purpose. Human bodies and farms alike are stations for the bio-amplification of proteins in an atomized supply chain driven by self-design.