Access the full report in pdf [here].

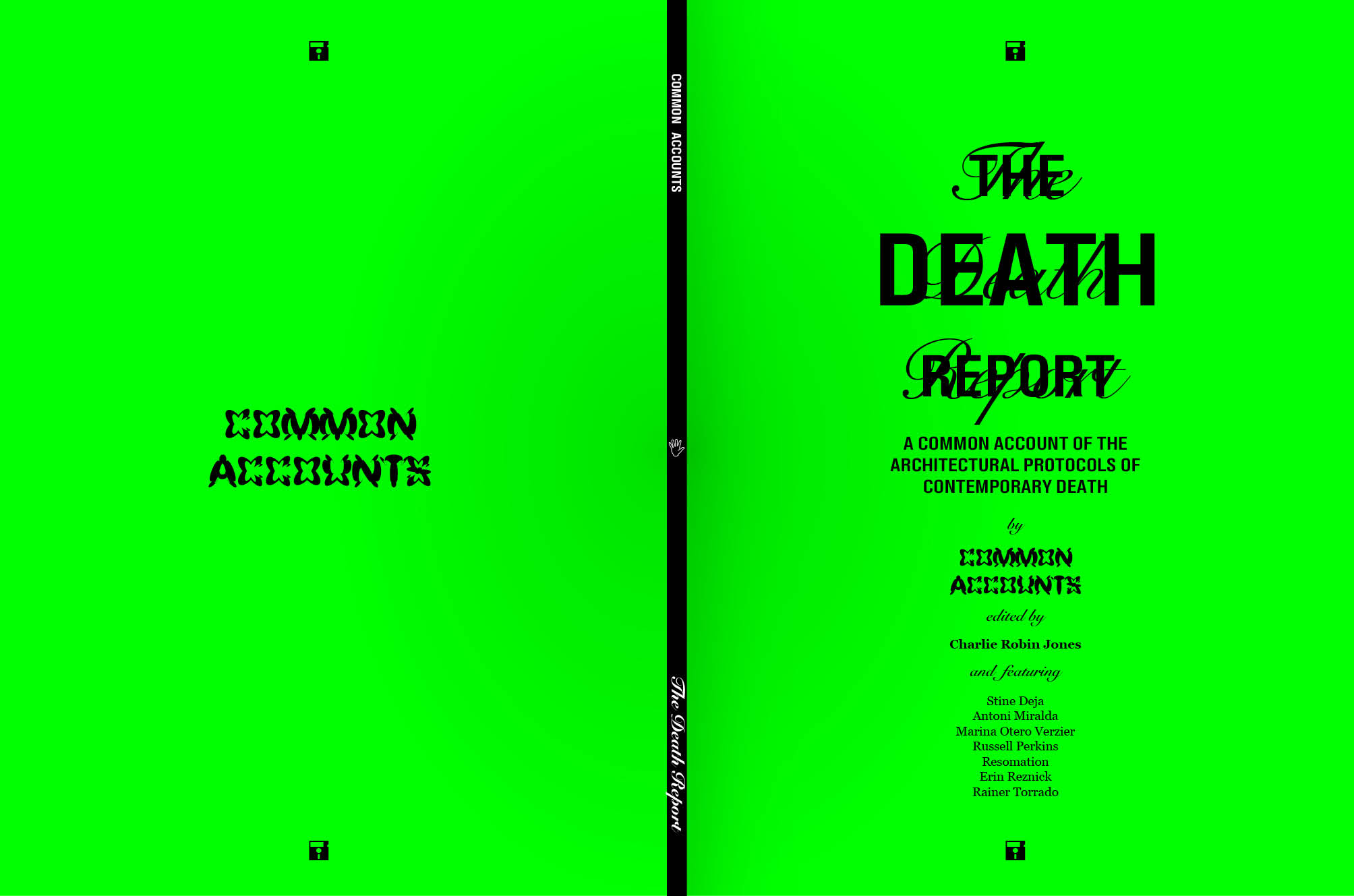

The Death Report is the result of eight years of work on the deep history and immediate future of architecture, memorial, death, and daily life. This report argues that death is a plastic force, and it examines smoothness, distance, visibility and value in contemporary death and dying in the contexts of biological end-of-life, self-imaging culture, the virtual afterlife, and war. It is edited by Charlie Robin Jones, and features contributions by friends and allies Stine Deja, Marina Otero, Antoni Miralda, Resomation, Erin Reznik, Russell Perkins, and Rainer Torrado.

PRELUDE:

The Anthropocene demands ritual. At least that was the central argument of our prior report, Planet Fitness. That text viewed the existential threat posed by climate change as a driver of anatomical design: as a force for climate fitness. And that text was concerned with—and suspicious of—prospective endings, much as this one is. Death, both at scales individual and collective, enacts ritual and modification to the human body. It enacts ceremony and layers it onto daily life. This is the case with the digital afterlife, too. The Death Report similarly develops a reciprocity between threat and resilience, and demise and ritual, now in the context of beauty cultures, self-imaging, bio-prosthetics, urban form, and digital environments serving everyday death. Very much aware of the popular obsession with endings, this report is concerned with the cultural and technological implications of the present and near-future of death as an industry, social practice, and biological event.

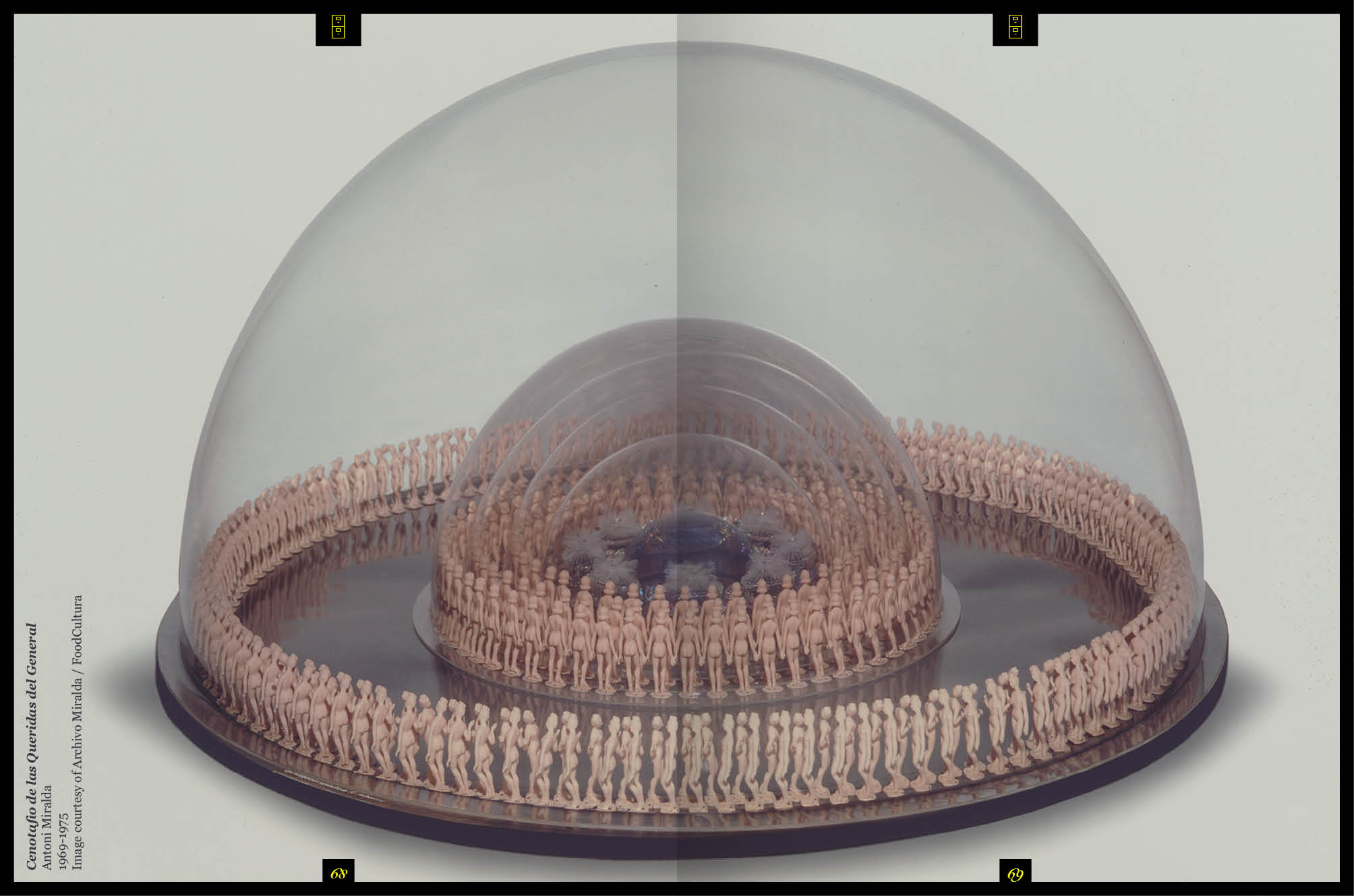

Death is an everyday product of design. It is as contingent as your running shoes, your air fryer, your file server, your quads, or your 800-square-foot apartment. The way we organize death, represent death, and calibrate its visibility manifests spatially. Venues for its formative consequence include funeral, remains disposal, mourning, memorial, and afterlife. The act of dying can be an act of design: like fitness and fashion, its ultimate goal is to construct the individual. And beyond the self, concepts of death have always brought themselves to bear on the material environment. This is as true for the shaping of daily life as it is for the shaping of cities.

Despite this, death has generally become distant and increasingly less visible in the everyday. Since the early modern period, death has been systematically designed out of the quotidian. There were good reasons for this: chief among them, hygiene and disease control, but also religious custom, fear, and political considerations that determine whose deaths we choose to see. Societies have largely surrendered death as a site for design action, because we rarely see it altogether, or because it is deliberately hidden

Two contradictory conditions—death’s widespread influence as a force of design and its progressive inconspicuousness—have today converged in a paradoxical status quo. Death is able to be managed discreetly, without major interruption for the living. Yet it lurks in the origins of so many parts of our built environment that death is in fact close at hand all the time: in the cool air you breathe in a climate controlled room, in the masonry that assembles your house, and in the treadmill at the gym.

For the purposes of this discussion, we will use the term “death” to broadly describe three intertwined concepts: the anatomical definition of human end-of-life; the social customs it mobilizes; and the digital realm it animates.

Death’s relationship to these sites is undergoing a stress-test. New medical and communication technologies complicate the precision of biological demise and therefore the definition of anatomical death itself. Emerging forms of human remains disposition and memorialization are contesting long-held attitudes around the solemnity of death, and consequently, how we govern death and calibrate its visibility in daily life. In this context, the digital afterlife—the virtual mirroring or extension of life—has emerged as a largely unmanaged force with enormous impact on the cultural and material world.

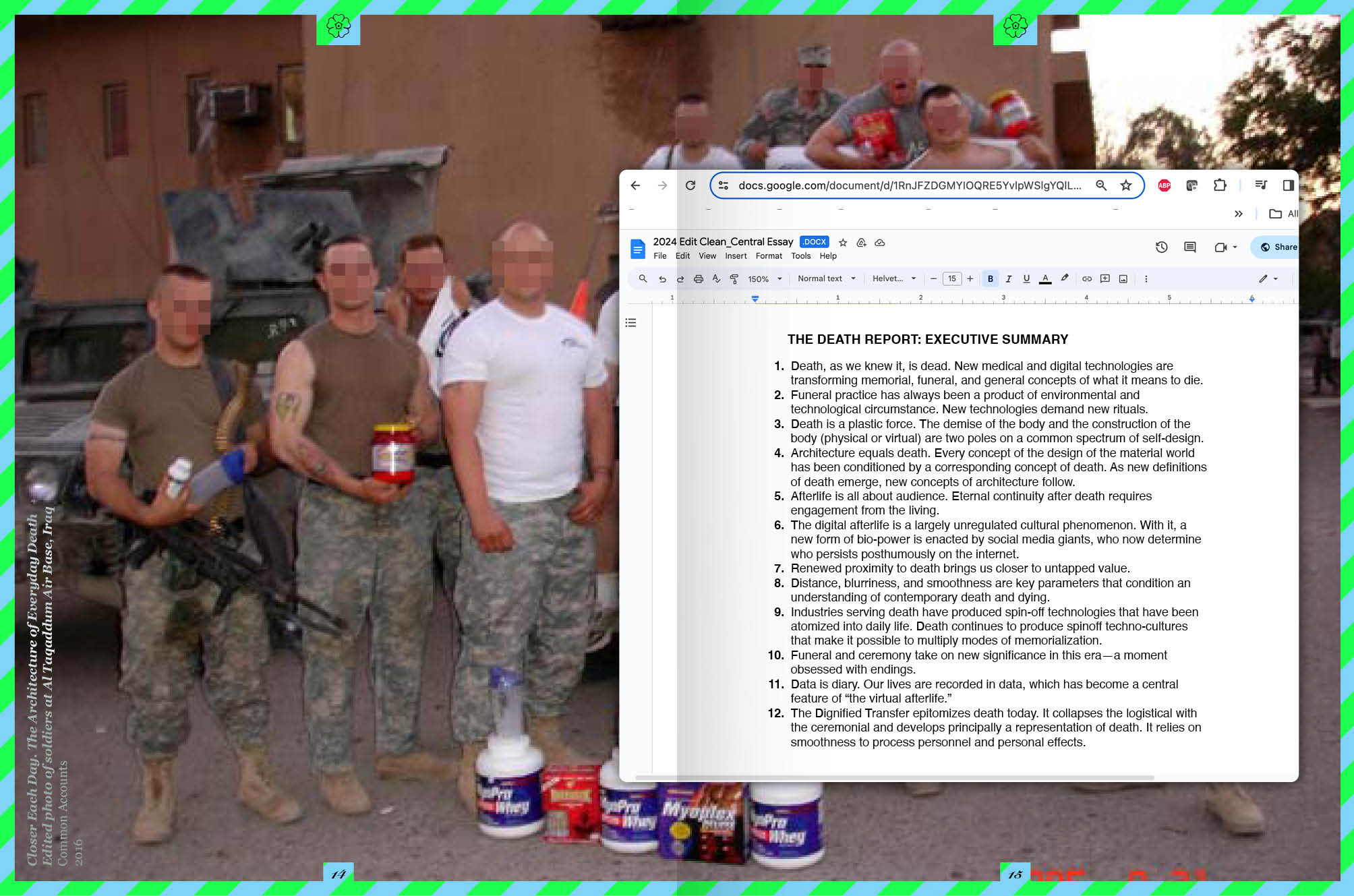

In the eight or so years that we’ve developed this work, we have largely insisted that our engagement with this subject matter be focused on an ordinary, everyday concept of death. We have been preoccupied more with considerations of unexceptional deaths, whose private tragedy doesn’t make the news: heart attacks, not air-strikes; old age, not trainwrecks. After all, death is challenging enough even when it is anticipated and our studio gravitates toward the exceptionality of the unexceptional: the paradoxically overlooked norm.

But in that same time frame, public tragedy —pandemics, warfare, now genocide— has returned again and again with a frequency that defies chance. The deep, inconsolable grief prompted by unjust, brutal, and terrible death has become all too common. As Sigfried Giedion, one of our central references and giant of 20th century modernist architectural theory, observed 80 years ago while writing Mechanization Takes Command, the quotidian is indelibly suffused with violence. And so, we must acknowledge and identify its traces whether they remain out in the open or under the radar. Even when it is subtle, once-removed, camouflaged, or idiosyncratic (caskets are lined with cushioning, after all), one cannot talk about death without at least the subtext of killing.